At seventy, Beverly Fishman re-examines the relationship between the body and time, synthesizing her past explorations and experiences around the concept of Equilibrium through a new series of works. She breaks away from the rigid visual order of geometric groupings, enabling the irregularities and rhythms to emerge--like musical notes in a score--endowing the forms more space and unpredictability.

Clad in highly saturated industrial colors, those forms evoke both the resonance of cultural baggage and a deliberate embrace of artificiality. Fishman continually synthesizes and interweaves color, material, and affect to create visual experiences that are both emotionally charged and aesthetically striking. Yet behind this seductive surface lies her deeper reflection on, and questioning of, various social systems.

As a multidisciplinary artist focused on abstraction, Fishman admires the courage and sensitivity of young female artist in speaking out and expressing themselves, while also recognizing the complex situation they face--just as she notes, “I also worry that certain battles are being fought again under new guises.” Her concern is not a rejection of any particular interpretive framework, but rather a consideration on how art can sustain depth and complexity, inviting multi-dimensional interpretations--both here and elsewhere--even within structural systems.

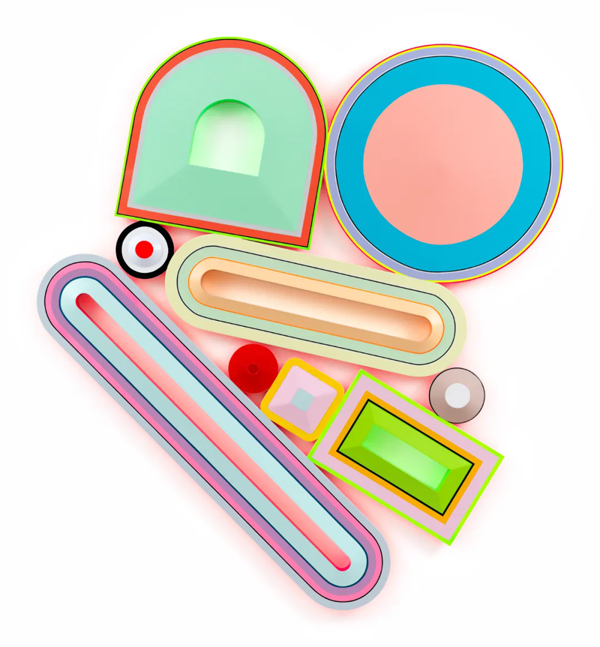

Equilibrium (C.B.M.P.), 2025, Urethane paint on wood , 72×66 3/8 inches (182.9×168.6 cm), (37585). Courtesy the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

Hu Lingyuan: You're turning 70 this year—how are you feeling right now, both personally and artistically? What made you launch a new solo exhibition at Miles McEnery gallery at this particular moment in your life?

Beverly Fishman: Honestly, turning 70 feels surreal—it's a number that carries weight, but I don’t feel the heaviness of it. I feel energized, maybe even more driven than I was in earlier decades. I’m more aware of time, yes, but not in a fearful way—in a focused way. The decision to launch a new exhibition now is part of that clarity. I’ve always used my work to reflect on systems—medical, aesthetic, cultural—and right now, I’m interested in equilibrium, in balance, in what it means to find form within flux. This moment in my life feels like a turning point, a kind of synthesis of everything I’ve explored so far, and I wanted the exhibition to reflect that.

New York, NY: Miles McEnery Gallery, “Beverly Fishman: Geometries of Hope (and Fear),” 8 May - 21 June 2025

Hu Lingyuan: About the exhibition’s title, I’m curious why you chose to juxtapose 'hope' and 'fear' through geometric forms? what’s the significance of placing 'fear' in parentheses?

Beverly Fish: The juxtaposition of hope and (fear) isn’t just poetic—it’s structural. These emotions aren’t opposites; they coexist. Especially in the systems I engage with—medicine, technology, design—hope and fear are often intertwined. We hope for healing, but we fear the diagnosis. We long for transformation, but we worry about what it will cost us. I’m interested in how abstraction can carry that duality, how something as clean and ordered as geometry can still pulse with unease. As for the parentheses around fear—yes, that was intentional. I didn’t want fear to dominate the title, but I didn’t want to exclude it either. It’s there, nested inside hope, almost like a shadow. It’s also a comment on how we often repress or bracket fear in our daily lives, especially in contexts where we’re expected to be optimistic or forward-looking.

New York, NY: Miles McEnery Gallery, “Beverly Fishman: Geometries of Hope (and Fear),” 8 May - 21 June 2025

Hu Lingyuan: In your latest “Equilibrium” series, I noticed that the compositions appear to have evolved. To me, the way the geometric forms gather and flow across the surface is almost musical—like notes in a score. Also, compared to previous works, those new pieces present a non-standardized and randomized state, rather than the previously more regular and uniform shapes, which often resembled large squares or rectangles. So, what prompted this visual shift?

Beverly Fishman: That's an incredibly perceptive observation. The shift in the compositions came from a desire to push past structure without abandoning it entirely. I’ve always been drawn to systems—pharmaceutical, technological, aesthetic—but I’ve also grown wary of how those systems control or confine. In Equilibrium, I wanted to let the forms breathe, to allow for more unpredictability. The musicality you mention—that’s very much intentional. I see these works almost like scores, yes, where color and shape become rhythms, dissonances, harmonies. It’s a conversation between order and chaos, and I’m letting myself embrace the irregularities.

Hu Lingyuan: On a technical level, it seems like finishing a composition like this isn’t easy—the title itself points to the challenge of balancing all these geometric shapes.

Beverly Fishman: Absolutely. “Equilibrium” is not just a title; it’s a task. Each composition is a balancing act, both visually and conceptually. I’m navigating tensions between form and color, symmetry and asymmetry, seduction and critique. There’s a point in the process where everything feels precarious—too much here, not enough there. And then, somehow, the piece resolves itself. Or maybe I just stop pushing. Either way, reaching that point of resolution is never easy, but it’s what makes the work feel alive.

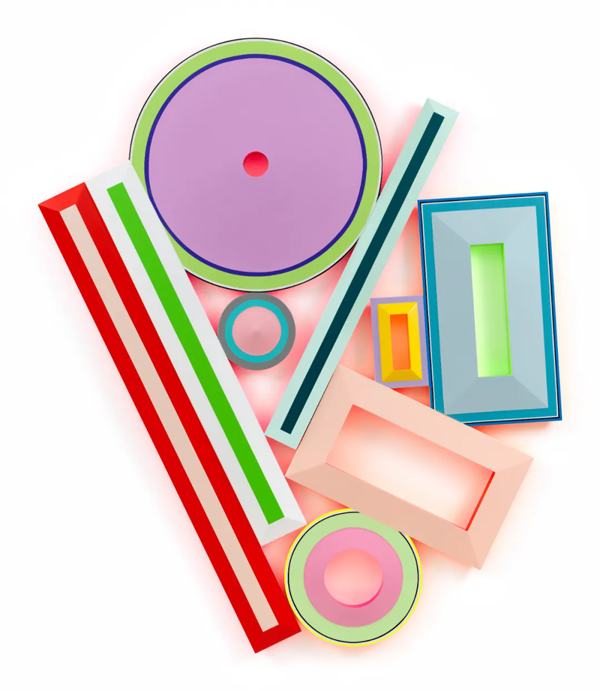

Equilibrium (J.S.C), 2025, Urethane paint on wood, 45×42 inches (114.3×106.7cm), (37586). Courtesy the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

Hu Lingyuan: I also like to hear more about your working process. Do you draw the composition digitally or start with sketches? And when it comes to painting, do you work intuitively, directly on the surface?

Beverly Fishman: The process starts with sketches and then collages where I experiment with color and form, shifting layers, flipping compositions. The collage studio is a laboratory for me—a place where ideas can move quickly. But when it comes time to translate that into paintings, the work slows down. Painting has its own demands—materiality, surface, technology, even logistics. And I like that friction. It keeps the work grounded.

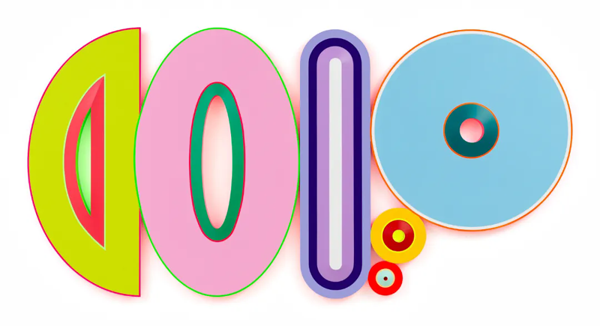

Equilibrium (P.P.9), 2025, Urethane paint on wood, 72×60 1/2 inches (182.9×153.7cm) , (37582). Courtesy the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

Hu Lingyuan: In your work, the color is incredibly vibrant and dynamic, often due to your use of industrial or fluorescent paints. But do you make adjustments afterward to better fit the overall composition? Are there colors you tend to use repeatedly, or ones you consciously avoid?

Beverly Fishman: Color is deeply intuitive for me, but it’s also strategic. I’m drawn to colors that signal warning, pleasure, sickness, ecstasy. The industrial and fluorescent paints aren’t just for brightness—they're about artificiality, about the ways the body is mediated through design and consumption. I do make adjustments, sometimes even late in the process. Certain colors—acidic greens, electric pinks, irradiated oranges—return again and again. I avoid “natural” tones unless I’m trying to complicate the palette. I'm more interested in synthetic affect.

Polypharmacy: Relief, Clarity, Composure, Liberation, Choice, Freedom, 2025, Urethane paint on wood, 44×89 inches (111.8×226.1cm), (37575). Courtesy the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

Hu Lingyuan: Compared to the circle, the square may suggest rigidity or even conflict—especially when rendered in high-contrast colors that further amplify its impact. How do you select color combinations for specific geometric shapes?

Beverly Fishman: That tension is precisely what I’m after. Squares, ovals, zips, and circles—each shape carries cultural baggage, whether it’s stability, danger, or healing. My goal is to layer those meanings, to make them vibrate against each other. The colors heighten that dissonance. I want viewers to feel both seduced and unsettled, to question why something so beautiful can also feel so clinical or even menacing. Geometry becomes a kind of language—a visual syntax that both communicates and conceals.

Hu Lingyuan: Your pieces appear pristine and refined, with hardly any traces of handcrafting. Is there something you're emphasizing or attempting to reveal through this minimalist strategy? Would you consider this a way of deliberate erasure?

Beverly Fishman: That’s a powerful way of framing it. Yes, there is erasure—of the hand, of the self. The works are smooth, controlled, almost antiseptic. That’s not accidental. I want them to look like they emerged from the same systems that produce consumer products or medical devices. At the same time, that perfection is a mask. The emotional and cultural content is embedded in the colors and the compositions, the way the paintings are designed. The minimalism is seductive, but beneath it is a complicated negotiation of identity, power, and vulnerability.

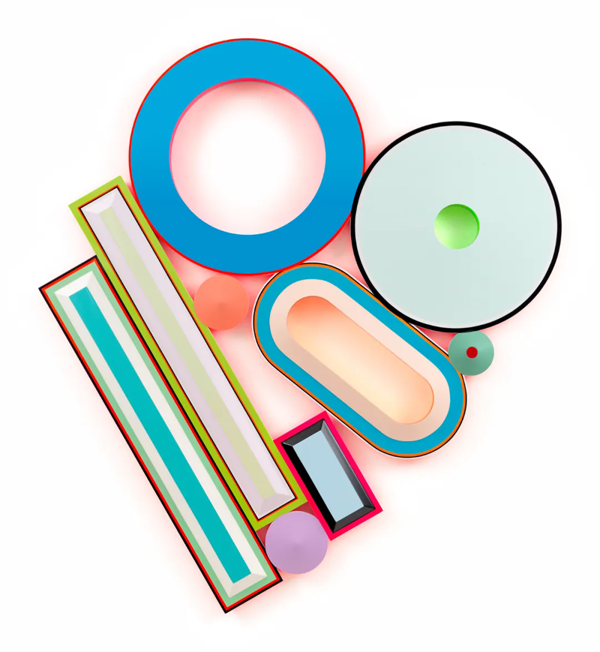

Equilibrium (B.O.C.C.), 2025, Urethane paint on wood, 64×58 inches (162.6×147.3cm), (37581). Courtesy the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

Hu Lingyuan: Your work has long incorporated pills and medical imagery, often through highly stylized, geometric forms. Do these shapes also carry cultural constructions of the body, identity, or gender?

Beverly Fishman: Definitely. Pills are not neutral. They’re vessels of control, healing, regulation. They affect how we experience our own bodies—especially for women, whose bodies are often medicalized, pathologized, or “corrected.” The pill, as an object, contains both liberation and control. I’m interested in how these forms carry not just aesthetic potential, but sociopolitical weight. They’re beautiful, yes—but they also speak to how identity is mediated, manufactured, and sometimes dominated and erased.

Hu Lingyuan: At this stage of your life, has your experience of your own body changed how you see or create art? With age, have you noticed any changes in what draws your attention, such as colors, perception, or other phenomena?

Beverly Fishman: Without question. Aging has made me more aware of time—of limits, yes, but also of depth. My body isn’t something I can ignore. It demands care, attention, and negotiation. That awareness filters into the work. I’m thinking more about impermanence, about cycles, about how the body metabolizes experience. Even color feels different now—more visceral, more urgent. Aging brings a heightened sensitivity, not a dulling. I feel more attuned to the world, not less.

Hu Lingyuan: Looking back, how has being a woman in the art world changed since you began your career? Do you think today’s younger female artists are facing different kinds of challenges—or perhaps repeating some of the same ones?

Beverly Fishman: There’s been progress, absolutely—but it’s uneven. When I was coming up, visibility was hard-won. Now there are more platforms, more opportunities, but also more noise. Younger female artists still face issues of erasure, of tokenization, of being read through gendered lenses. The language has changed, but the structures—patriarchal, capitalist—persist. I admire their courage, their fluency with identity politics, but I also worry that certain battles are being fought again under new guises.

Hu Lingyuan: How do we interpret the last sentence? Do you think this also reflects a certain constraint imposed by the current discourse? In your view, how can artists authentically express personal experiences, such as those grounded in gender, without being reduced to a symbol?

Beverly Fishman: That’s a very real tension—and one I’ve felt myself. On the one hand, there’s a deep need to speak from lived experience, to embed the realities of gender, body, and identity into the work. On the other hand, there’s the fear that once you do, you’ll be flattened into a “woman artist,” or your work will be read only through that lens. That kind of reduction is its own form of censorship. I do think this reflects a constraint within the current discourse. The art world loves to categorize—it’s a system of labeling, and that can be both clarifying and limiting. But I believe the answer is to stay rigorous and honest in the work. If the work comes from a place of complexity—of contradiction, vulnerability, ambivalence—it resists easy symbols. I don’t think we have to avoid identity to avoid simplification. We just have to refuse to let the work be only about identity. For me, the challenge is to make work that contains gender, history, emotion, critique—but doesn’t resolve into a single meaning. That’s where the power lies. Ambiguity can be a form of resistance.

Beverly Fishman is an artist who adopts the language of abstraction to explore the body, issues of identity, and contemporary culture. Her career-long investigation draws upon medical imaging, pharmaceutical design, and the history of modernist painting. She is the recipient of many awards, including the National Academy of Design Academician Award; an Anonymous was a Woman Award; the Hassam, Speicher, Betts, and Symons Purchase Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship; a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award; an Artist Space Exhibition Grant; and an NEA Fellowship Grant.

Fishman’s work has been the subject of over forty solo exhibitions at galleries in New York, London, Paris, Berlin, Thessaloniki, Chicago, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and Detroit. It has also been shown at the Chrysler Museum, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Columbus Museum of Art. Her work is represented in many collections including the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University; the Mint Museum; the Cranbrook Art Museum; the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art; the Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation for Art, the Pizzuti Collection. Her work has been reviewed in numerous art magazines, newspapers, and scholarly publications, including The New York Times, The Brooklyn Rail, Artforum, Huffington Post, Modern Painters, Artnet Magazine, Wallpaper, NY Arts Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, and Art in America. Between 1992 and 2019, she was Artist-in-Residence and Head of Painting at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. She is represented by Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY; Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, CA.